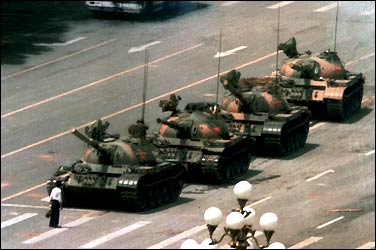

TOMORROW is the 15th anniversary of the massacre of student demonstrators in Tiananmen Square. During the six years I spent in prison after the massacre, much of it in solitary confinement, I had ample time to reflect on whether we – the leaders of China’s 1989 democracy movement – made a mistake in encouraging the protests that culminated in the tragic events of 4 June.

Again and again, I have asked myself if there was another path that could have avoided the bloodshed. And whether, by bringing students and other ordinary citizens on to the streets to confront the Communist leadership, we frustrated the plans of reformist leaders – such as the former Communist Party general secretary, Zhao Ziyang – to engineer a peaceful transition to a democratic China. It’s a question I’ve also often been asked during my public appearances in the US, since I was forced into exile in April 1998. Emphasis added by me.

Now, reflecting on the events of 15 years ago, it is clear to me as never before that the Tiananmen massacre was an unavoidable step in the long path to a free China, and that true political reform can never come from within the Communist Party.

Indeed, one of the real tragedies of 1989 was not that we jeopardised the efforts of so-called reformist leaders. Rather it is that they never had the vision or political will to lead China toward democracy.

The events of 4 June were a turning point for me and other members of what we call “The 1989 Generation”. Encouraged by the brief relaxation in the political environment in Beijing in the months before the killings, which had even made it possible for me to hold workshops on democracy, we harboured false hopes that change could come from within the Communist Party. It was this fantasy that emboldened us to take to the streets, calling on the government to fight corruption and take steps toward a free society. We petitioned the leadership in the hope of triggering a top-down reform.

Yet the response of “reformists” in the leadership was disappointing, to say the least. Had their hearts been with us, they would have surely seized this unique opportunity to support publicly our calls for democratisation.

Instead, they continued to hide behind closed doors. Only after he had already been outvoted in the Politburo standing committee did Mr Zhao finally come and visit us in Tiananmen Square. And when our modest demands were answered with gunshots on the night of 4 June, it shattered any remaining illusions.

The experience of the 15 years since then has confirmed what we failed to understand in 1989. Namely, that Communist leaders, be they conservatives or reformists, are all wedded to retaining the current political system, complete with its problems such as corruption and lack of accountability.

Look, for instance, at how even relatively enlightened officials such as Premier Wen Jiabao – who visited us in Tiananmen Square in 1989 – and President Hu Jintao have shied away from political reform since taking office. Instead, the issue remains a taboo subject in Beijing. And far from easing its iron grip on all forms of political dissent, the new leadership now seems intent on extending it to Hong Kong.

In the past, the Communist Party has reversed its official verdict on several other major political events in modern Chinese history. The Cultural Revolution, hailed by Mao Tse-tung as a great proletarian movement, has long since been repudiated. Another popular protest that also led to violent scenes in Tiananmen Square, the demonstration on 5 April, 1976, against the leftist leaders known as the “Gang of Four”, was also initially suppressed and labelled as counter-revolutionary. Within two years, that verdict had been reversed and it was recognised as a legitimate public protest.

Yet when it comes to 4 June, there has been no change even after 15 years. That’s because Messrs Wen and Hu realise that re-evaluating the official description of the 1989 movement as counter-revolutionary would shake the foundations of the Communists’ grip on power.

But avoiding the issue will not make it go away. On the contrary, the cries for justice are getting ever louder.

In recent months, the group of parents and relatives of those killed in 1989, known as the Tiananmen Mothers, have been gaining increasing domestic and international support in their fight to reverse the official verdict on the 1989 movement. They have been joined by Jiang Yanyong, the heroic doctor who blew the lid on China’s initial cover-up of the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome last year. In an open letter to the Chinese leadership, Dr Jiang recounted what he witnessed on the night of the killings and called on the government to revisit what he called the worst Communist crimes since the Cultural Revolution.

The continued failure of the Chinese leadership to address the issue only increases the risk of further violent eruptions in the future, especially at a time of growing social discontent. With unemployed workers struggling to survive without any form of welfare benefits, residents forced from their homes without proper compensation and farmers living in extreme poverty as they shoulder unfair tax burdens, China is a tinder box which could be set on fire by the slightest spark.

Worse still, until the leadership confronts the past and re-evaluates the official verdict on the 1989 movement, there is always the danger that it could resort to such violent methods again to suppress any future protests.

One positive development is that, since the early 1990s, shoots of civil society have begun to sprout within China. As more Chinese enter the private sector, the state is no longer able to control every aspect of daily life in the way it used to.

On the contrary, people are starting to recognise the importance of monitoring the state and making government more accountable. And as the internet and modern telecommunications have become part of everyday life, it’s become easier to break through the government’s control of news and information and to organise campaigns for basic rights, be they the right to private property or freedom of speech. This provides a stronger basis for continuing the fight for democracy in China.

Fifteen years after the massacre, the 1989 democracy movement remains as much a part of my emotional present as my past. The movement and its aftermath have consumed the idealism and passion of my youth, and the fight for a reversal of the official verdict has become a goal which I can never abandon.

The 1989 student movement played an invaluable role in pointing out the path to democracy in China. Without it, we would still be clinging to the myth that a small group of enlightened Communist officials could rescue China from totalitarian rule. Instead, we have learned from our mistakes that year, and realised that China’s democratisation must be a bottom-up process, driven by forces outside the Communist system.

And when that happens, as it inevitably will, I will be able proudly to say that we, the 1989 Generation, were part of the process that brought freedom to my home country.

There’s nothing I can add to that, except Thank You.

Comments