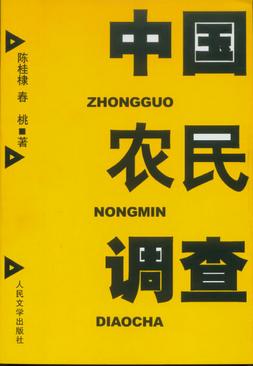

The publication of this survey on the plight of Chinese peasants was seen just a few months ago as a major breakthrough. It seemed to signal a new willingness on the part of populists Hu and Wen to actually encourage dialogue on a taboo subject. It was, for me at least, unbelievable. They were actually exposing the abuses against the peasantry! So there was little surprise when we heard weeks later that the book had been banned, but there was a lot of disappointment.

Kahn presents the first detailed article I’ve seen on this sad story.

The book describes one farmer, named Ding Zuoming, and his decade-long campaign to enforce central government directives limiting taxes and fees. Although the Beijing authorities reviewed and approved his complaints, the local police found an excuse to arrest him, the book says. They beat him to death in custody.

The authors tell the story of Zhang Keli, described as an idealistic public official devoted to fighting poverty. Over time, he found that fellow village chiefs had found ways to enrich themselves and their relatives, even while they won promotions.

“He felt like he would be an idiot not to take his share,” Mr. Chen and Ms. Wu wrote.

The book became an unexpected best seller earlier this year. Whether that was because it named names in exposés about the underside of China’s boom or because its publication coincided with an effort by Mr. Wen to promote new rural policies is unclear.

Chen Xiwen, the deputy director of the Central Finance and Economics Leading Group, a high-level government policy-making committee, and the man considered China’s foremost rural policy expert, said in a recent interview that he had bought two copies, one for the office and the other to keep at home….

Propaganda authorities evidently felt the book went too far. Even as a media frenzy built in March, the government-owned publisher got a verbal order to cease printing. Media coverage ended instantly. The authors estimate that the book has sold as many as 7 million copies, but they earned royalties on only the 200,000 legal copies sold before the ban.

More disconcerting to the authors, a disgruntled local official named in the book, Zhang Xide, filed a libel suit against them seeking $24,000 in damages. As Chinese officials rarely file court actions without the approval of superiors, Mr. Chen and Ms. Wu say they effectively face prosecution by Anhui Province.

That would be the final irony, if after all the exultation and dismay the authors end up being punished. Sometimes it seems like part of the culture, putting the nation’s heroes and whistleblowers in jail.

Reform in China so often seems to resemble — pardon the expression — a Chinese fire drill. They give us a strong hint of improvement, we get all excited, articles come out, the blogs go nuts, we all wonder, Is this it — the real thing?? And then it just evaporates as though it never happened at all, and we’re back where we were before. It’s exhausting. It’s dizzying. And it’s always exactly the same.

UPDATE: I edited this post, changing an earlier sentence where I said the books authors might face going to prison; if they are punished, they would probably have to pay a high fine, and not face prison time.

Comments