Xujun Eberlein grew up in Chongqing, China, and moved to the United States in the summer of 1988. After receiving a Ph.D. from MIT in the spring of 1995, and winning an award for her dissertation, she joined a small but ambitious high tech company. On Thanksgiving 2003, she gave up tech for writing. Her debut story collection Apologies Forthcoming won the 2007 Tartt Fiction Award and was published in May 2008. You can buy the book here.

The stories in Apologies Forthcoming deal with the Cultural Revolution, which defined the generation now coming to power in China. Xujun departs from the more typical “victim literature” about the CR, and the stories show a broad range of perspectives, actions and responses to the turmoil of the period.

Lisa: Tell us about the title of your collection, “Apologies Forthcoming.” Why did you choose it?

Lisa: Tell us about the title of your collection, “Apologies Forthcoming.” Why did you choose it?

Xujun: I had considered calling the book Men Don’t Apologize, but some writer friends objected. They pointed out that people would probably expect a feminist treatise, while I’m not a feminist at all. And the stories don’t actually have any agenda other than realistically portraying human behavior and psychology at a particular time. While that namesake story is about several men and a woman, the idea of apologizing for, or even acknowledging participation in, activities during the Cultural Revolution cuts across the sexes. Apologies Forthcoming was actually the publisher’s suggestion and I like it, though I am not sure we will ever see the apologies. ☺

Speaking about apologies, two years ago I interviewed a few ex-Red Guard leaders in Chongqing, who had been in jail for more than a decade and now are businessmen. I wrote a short journalism piece about this, which you can read here.

Let me just quote one of the men here – he said, “We castigated the capitalist roaders for two years. They punished us for many more.” He didn’t think he ought to apologize to anyone at all, and you have to acknowledge his point.

Lisa: Related to this question of apologies…my first time in China was in 1979, so the Cultural Revolution was still very present in peoples’ lives. At the time I felt like the country suffered from a massive emotional depression from the after-effects of so much mass trauma. And a number of Chinese people I met told me about some of their experiences during the CR – some very traumatic and personal things. I’m guessing this was because I was a young foreigner, not involved and therefore safe to confide in. Did you talk about your experiences with fellow Chinese? To what extent did people feel they could honestly speak about what had happened to them and what they had done during this time? Did you talk to anyone about your own experiences?

Xujun: Oh, plenty of people talk about their sufferings, but few mention their roles as participants. One representative example is the memoir Wild Swans. I admire the book’s writing, but as I mentioned in my Amazon review for it, I wish the author were more honest. Readers relish suffering stories, but suffering stories alone provide limited insights into human behavior.

It also occurs to me that few westerners know the subtleties and nuance surrounding the participating parties in the CR. I once did an informal poll among writers I workshop with on what they thought of the Red Guards, and the answers were pretty much uniform with the representative one being “pretty much the same as the Hitler Youth.” This is quite baffling and at the same time very interesting. As we know (I’m aware of the pitfall of generalization) Americans hate the communist government of China; but did they know the biggest thing the Red Guards did was to break China’s state apparatus? Should a communist hater applaud or condemn that? There is just no simple black-and-white answer.

Another thing is that the Red Guards consisted of an entire generation of students from middle school through university, and though viewed as a collective by westerners, there were many different factions emerging, converging, breaking down and reorganizing over times.

The Red Guards did have a hand in lots of violence, yet the individual members were often idealists. This complexity seems beyond the average outsiders’ comprehension. It is very hard for someone to understand another culture without actually experiencing it. But the real problem is not the limitation in understanding – everyone has limitations; it is failing to recognize limitations. Too many people are vocally righteous about other cultures they know little about, that is the problem.

As a writer, however, I am more interested in human behavior and the mentality that leads to it. I’m not interested in pointing fingers because what does that do to increase understanding? I think as realistic fiction the story “Men Don’t Apologize” departs from the usual victim literature and takes one step further in exploring human nature and the different behavior that manifests between ordinary and extraordinary circumstances.

I don’t want to digress too far on this topic, let’s just say that, as far as political conflicts are concerned, victims and victimizers can easily switch positions. The distinction between victims and villains is very unclear and my stories show a broader range of behavior beyond suffering.

Lisa: “Snow Line,” the opening story in the collection, is set in Chengdu, a city I’ve spent some time in and really love. Even in the immediate aftermath of the Cultural Revolution, it felt a lot more relaxed and open to me than most of the cities I visited. It’s surrounded by a lot of natural beauty, and places like Qingchengshan, which is considered one of the birthplaces of Daoism.

I notice that flowers are a recurring motif in “Snow Line,” and I’m curious if this is something that connects specifically to Chengdu.

Xujun: Yes, Chengdu! My favorite city of all! (I hope my Chongqing townsmen will forgive me for saying this.) In the north it is Beijing and in the south it has to be Chengdu. Do you know a saying, “少不入川,老不出川” – “When young don’t enter Sichuan; when old never go out of it”? In this saying “Sichuan” actually means its capital Chengdu. Chengdu is such a relaxed and cultured city, a young man would only be spoiled there and never work hard, is what the saying means. But it is heaven for a relaxed and richly cultured life. Every year I go back for a visit, I can’t help but wonder how such a free and at leisure population make their livings. Yet they live leisurely on. All my close friends from Chongqing have moved to Chengdu by now.

And yes, Chengdu is a true flower city. Everywhere on the streets and in every season you see flower girls and flower stores. Even Chengdu’s air is fragrant and colorful. You don’t see or smell this in Chongqing for example. Don’t get me wrong, I love Chongqing, too, but that’s for its ragged hilly paths and two legend-filled rivers.

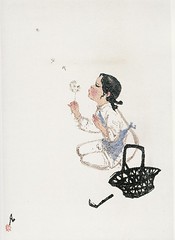

You can probably sense my love of Chengdu from descriptions in “Snow Line.” But the reason I placed “Snow Line” as the opening story is because of the artwork, “Dandelion.” The artist, Mr. Wu Fan, is a renowned “literati artist” in Sichuan, a very classic kind. “Dandelion” was his signature work and won a gold medal in the 1959 international block prints competition. During the CR the gold medal became a criminal indictment for him and nearly killed him.

Mr. Wu is a friend of my parents, and his daughter and I are friends. The genesis of “Snow Line” actually came from the daughter; she had modeled the little girl in “Dandelion.” I thought the artwork would add a nice dimension to my story, so I asked for permission to include it from Mr. Wu Fan, and he generously agreed. I ended up using three works from him, each fits nicely with one of the stories. His daughter did the sketch for “Men Don’t Apologize.”

When I was in college, every summer I would go to Chengdu and spend time with the Wu family. The mother, an oil painter, would bring her two daughters to paint from nature in Huanhua Xi – Wash-flower Brook, and I would go with them. Those were some happiest times of my youth.

Lisa: The first time I was in China, one of the phrases I learned right away was “work unit.” The idea that so many decisions about one’s personal life could be made by one’s place of employment was very foreign to me. “Snow Line” presents a typical situation in the China of the late 1970s to early 1980s, where a woman lives in the factory in which she works. The whole notion of privacy and personal space is very different from the West. So a two-part question – when you moved to the US, was this a difficult adjustment to you? And do you think that China as a society has moved towards more “Western” notions of privacy?

Xujun: Hehe, the phrase is still there, on everyone’s lips. And you ask an interesting question. When I am writing stories I wear the hat of the times, and this all seems perfectly natural. However, when I think about actually doing something like living in a printing factory it does seem pretty strange. It is curious how quickly I became accustomed to the easy (and private) life in the US. I don’t think I could make the adjustment in the other direction nearly so quickly. There is a Chinese word for that – xiguan – that would be used only in one direction.

China has changed a lot since the early 1980s, when I was in college. There is surely more privacy in people’s lives now. For example the question “How much do you make?” was as common as “Have you eaten?” in conversation when I lived in China. Now you hardly ever hear the former spoken. ☺

However I don’t think Chinese will completely adopt the Western notion of privacy – that would be very sad anyway. Neighbors still love to “chuan-men” (drop-by) without having to first set appointments, for example.

Lisa: “Feathers” tells the story of a girl losing her older sister. In a way it is a typically “Chinese” story, a Cultural Revolution tragedy. But on the other hand, the family dynamics transcend the cultural particulars and deal with universal themes of loss, denial and suffering.

Xujun: I think that is an important observation, and I think it may apply more broadly than just this story. People have a lot in common with one another, and a lot that sets us apart. “Feathers” is about family and dealing with tragedy, and this is an area where similarities are much stronger than differences. Still, the story tells a Chinese way of dealing with things, for example making up stories so the grandmother wouldn’t know about her grandchild’s death. I remember workshopping the story and some American friends just couldn’t understand why the lying was necessary. Some things that might stand out to a Western reader would simply be background to a Chinese reader.

You know, this story is close to my heart. And go back to your question earlier if I talked to anyone about my own experiences during the CR, I was a child when the worst thing happened to my family – my big sister’s death. She was a 16-year-old Red Guard. I had to safeguard my 75-year-old grandmother from knowing the bad news, just like in the third-person story “Feathers.” Imaging a 12-year-old girl running around bare her teeth like a fierce cat hissing at any gossipy neighbor who dared to mention the incident. That practice trained my habit of silence; for more than three decades I did not talk to anyone other than my diary book about the incident. I never shed tears either. I cried for the first time in 2002 when I began to write the memoir piece “Swimming with Mao”.

One question a reader raised was if my loyalty to my sister might have impeded my condemnation of the Red Guards. However, though my sister was both a participant and a victim of the CR, she foremost was my dear sister and no political identification could change that. This became never so clear after I started to write about her.

The story also reflects my aversion to heroism. When my sister died, her comrades called her a “hero.” As a child I was very confused by the notion that a life was tradable with the title “hero.” I just wanted my dear sister back – who cared what her title was?

Lisa: I particularly liked “Watch the Thrill,” with its two bored neighborhood boys who are looking for excitement. It’s not that they are bad or evil, they just seem to lack the capacity to make moral choices, and there are no adults around to guide them. This had a lot of resonances to me, both to kids growing up here and now without adequate parenting and to figures in classical literature – “Lord of the Flies” comes to mind.

Xujun: It is interesting you should mention this. There is a broader belief that youth and innocence should go hand in hand. In this story I wanted to portray not that the boys were bad, but that they really weren’t concerned about the concepts of good or bad, but just interesting or boring. Becoming invested in good and bad requires some reasonable landmarks of this type of judgment, and those landmarks were missing when these boys were raised. This makes the emergence of any sort of morality difficult.

Lisa: Tell us about the title of your collection, “Apologies Forthcoming.” Why did you choose it?

Lisa: Tell us about the title of your collection, “Apologies Forthcoming.” Why did you choose it?

Comments