There have been a dizzying array of articles over the past two weeks about reform in China — all kinds of reform, such as opening up about air pollution, to what extent Xi Jinping will serve as a “reformer,” calls by reformers for China to live up to its constitution, Southern Weekend calling for reform of censorship and forced propaganda. It’s been hard to absorb it all, and even harder to evaluate what all this noise means. And really, there’s only one answer to all these questions and claims: It’s too soon to tell. And, No one knows.

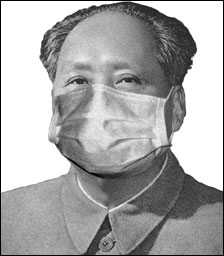

I’ll never forget the mood in China after Hu Jintao took office in 2003. There was something akin to euphoria among some English-language China blogs (now all gone). Hu had just lifted the curtain on the government’s mismanagement of SARS and all but admitted its malfeasance in deceiving its people about it. Heads rolled. Surely this was proof that China now had a reformer in charge. Wen, too, immediately established himself as the good leader, the friend to the little man who would initiate reforms to ease the plight of the poor and the disenfranchised.

Wen’s image as a reformer never really died, whether he was one or not. Hu’s image as a reformer, on the other hand, was painfully short lived, and soon we were back to the usual government propaganda, censorship and repression. Censorship only got worse. At the time, I argued that reform under Hu would be impossible simply because it would threaten the one-party state, and reform didn’t seem to be the people’s No. 1 priority.

Things seem very different at the moment, with calls for reform coming from so many different directions. So with Xi Jinping I’m not placing any bets. Maybe the whole point of this post is simply to say I don’t know. The only thing I can say is that it will be fascinating to watch. It would be a cliche to say China is now at an inflection point, but I believe it to be true. My guess, however, is that we will see change occur only at glacier speed as the party deals with how to enact reform while holding onto power with an iron fist.

Possibly the most pessimistic piece I wrote on the subject can be found here. It’s written by a China watcher I have huge respect for.

Future historians wondering exactly when the PRC entered its pre-revolutionary phase may focus on a series of speeches that General Secretary Xi Jinping delivered behind closed doors to the Communist Party elite after being promoted to the top slot in the leadership. It was rumored early on that his tone was not encouraging to anyone hoping for an incremental transition to the rule of law with wider scope for civil society and greater accountability in government. Now Gao Yu has provided a few quotes from one of these speeches in an essay which Yaxue Cao has translated. In these fragments we glimpse a ruling class that not only is prepared to defend its privileges with force but anticipates the need to do so, and views proposals for reform as threats to its grip on power.

I urge you to visit the site and see the quotes from these speeches. They won’t encourage you to believe this is a government that will lean toward compromise.

At the moment, things look so positive for reform that reformers are speaking out openly about the need for China to recognize and enforce its constitution, a document that has proved infinitely irrelevant ever since it was enacted.

Now, in a drive to persuade the Communist Party’s new leaders to liberalize the authoritarian political system, prominent Chinese intellectuals and publications are urging the party simply to enforce the principles of their own Constitution.

The strategy reflects an emerging consensus among advocates for political reform that taking a moderate stand in support of the Constitution is the best way to persuade Xi Jinping, the party’s new general secretary, and other leaders, to open up China’s party-controlled system. Some of Mr. Xi’s recent speeches, including one in which he emphasized the need to enforce the Constitution, have ignited hope among those pushing for change.

A wide range of notable voices, among them ones in the party, have joined the effort. Several influential journals and newspapers have published editorials in the last two months calling for Chinese leaders to govern in accordance with the Constitution. Most notable among those is Study Times, a publication of the Central Party School, where Mr. Xi served as president until this year. That weekly newspaper ran a signed editorial on Jan. 21 that recommends that the party establish a committee under the national legislature that would ensure that no laws are passed that violate the Constitution.

One very astute article says we’re all asking the wrong question. It shouldn’t be whether Xi will be a reformer, or what kind of reforms he’ll initiate and when.

Better questions are needed in order to produce more useful analyses and forecasts of China’s political development. Such analyses should start by recognizing two facts: First, the new leadership’s various initiatives and pronouncements after taking office indicate that it fully accepts the need for change. Second to quote the American political scientist Samuel Huntington, the leadership is clearly aiming at “some change but not total change, gradual change but not convulsive change.” In short, the leadership wants controlled reform, not revolution or regime change.

Huntington has argued that implementing reform is far more difficult than staging revolution. The methods, timing, sequencing and pace of changes all need to be carefully managed. If not handled well, reform will lead not to stability but to greater instability and may serve as a catalyst of revolution. China’s experience with reform and revolution through history, especially its modern history, certainly lends support to this argument.

Finally, for an exhaustive and incredibly well-researched look at China’s leaders’ challenges maintaining stability in the face of social pressures, this article is a truly must read. Just a sample, from an essay by the Director of the Social Issues Research Center at the China Academy of Social Sciences Rural Development Institute. Reform seems to be on everyone’s lips at the moment.

The key to stability preservation lies in resolving the standoff between government attempts at stability preservation and popular efforts at rights protection. Essentially, rights protection is not in conflict with stability preservation. Quite the contrary, rights protection is the basis of stability preservation, as the process of rights protection is also one of stability preservation. The recognition and protection of people’s basic rights form the sole foundation upon which sound and lasting stability preservation can be achieved. Indiscriminate violation of these rights in the name of stability preservation will yield a stability that is fragile and ephemeral. The construction of a fair and just system for social distribution is the crux of stability preservation in contemporary China, but this requires first addressing the issues of interest imbalance and interest articulation. The frequent instances of rights protection and emerging rights discourse in today’s China have generated a gradual awakening of a rights consciousness among the Chinese public. This presents a golden opportunity to institutionalise a mechanism for rights protection, to open channels for the articulation of citizens’ interests, and to level the playing field for laborers and disadvantaged groups in the areas of interest aggregation and policy-making. If seized, this opportunity would enable the rapid realisation of true harmony and stability. The rationale is simple; effective stability preservation is dependent upon rights protection, which in turn requires a mature and institutionalised claims-making mechanism.

I know, that’s a lot of links and a lot of quotes. My point being that there is rather suddenly a tidal wave of discussion about reform and how it might work. I feel more optimistic than I did when Hu took office because this time the demand for reform appears to be far more extensive, coming from all segments of society. Even if a Pew Research Poll proves that most Chinese are charmed by what they see as the infallible leadership of their leaders, a lot of them seem to believe it’s time their leaders initiate broad-based and meaningful reform.

Comments