As China gets ready to celebrate Mao’s 120th birthday there have recently appeared a slew of articles on China’s current relationship with the Great Helmsman. One of the most interesting was in the Global Times, warning about “Mao denigration,” a campaign to malign Mao, initiated mainly by Westerners who hate China.

That Mao is a great man has a strong foundation in Chinese society. Some think Mao has had an infamous reputation in society. This is only a naïve delusion of these people….

There is no historical or current evidence that is convincing enough to denigrate Mao. Voices that completely deny or support him are both highly polarized. Currently, the demonizing voices are mainly from the West, which also criticizes China’s socialist system.

The article disingenuously dances around the dreadful things Mao did by noting “his personal leadership style has its own limits,” and not unsurprisingly bestows on him the usual cliches — he brought China independence, he set the stage for China’s current prosperity, people’s lives improved under Mao, and there is, needless to say, no references to Mao’s experiments like the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. It even claims Mao’s revolution “put it [China] on the right track of human rights development.”

Human rights development? Mao did have some solid achievements, but I don’t see “human rights development” among them. He did help give China a backbone as it freed itself from foreign domination. He did help give women greater equality. But as in any discussion of Mao’s achievements, the question needs to be raised, “Yes, but at what cost?” China is still reeling from the effects of his pet projects that caused the death of millions, and that forced generations of Chinese to eat a lot of bitterness.

But that’s okay; you can’t make an omelet without breaking a few eggs, and as the GT article concedes, “A revolution always has its cruel side, as did the Chinese revolution led by Mao.” That cruelty doesn’t really matter much, it says; what matter is the result of the revolution. It’s funny, but my own reading on the story of the revolution is that the result of the revolution up until the time Mao died was total chaos and misery, until Deng stepped in and cleaned up the colossal mess Mao had made of the country.

But the Global Times article accurately reflects, to a large extent, what a lot of ordinary people in China believe about Mao, that he made life better, that the Mao years were relatively corruption-free — many of the laobaixing will even go so far as to say they wish Mao were in power today. This article in the SCMP examines this phenomenon.

Today, reverence for the late leader is on the rise. President Xi Jinping often pays tributes to Mao and looks to him for inspiration to manage the country. Ordinary people, especially from the bottom social strata who have not benefited from the country’s economic boom, miss his reign and some even set up shrines at home to worship him. Statues of the great leader continue to be erected across the country with fanfare.

“If there is one man, one vote now, the leftists would get most of the votes,” says Du Daozheng , the 90-year-old publisher of liberal political magazine Yanhuang Chunqiu and once a loyal Mao follower….

Xi launched “rectification” and “mass line” campaigns to fight corruption and restore grass-roots support. He also revived the tradition of “self-criticism” sessions in which cadres pillory each other’s failings.

Liang Zhu, an expert on Mao Zedong Thought and former deputy head of Peking University, has argued party officials were showing a “a correct proletarian view of power” by returning to Mao. “Mao insisted that ‘to serve the people’ is the basic mission,” he wrote in a recent essay.

I have to wonder how Mao’s blood-stained hands and cutting China off from the outside world served the people, but I also have to acknowledge that most Chinese people believe that Mao was good for their country. And I understand, the last thing they want to hear is Westerners criticizing Mao. But China’s refusal to acknowledge the very dark side of Mao’s tragic policies is a cause of constant fascination among China watchers and will continue to spawn op-eds and articles examining how this could be so.

The Washington Post also writes today about the current Mao fever that’s taken hold of China.

Mao is everywhere, even after death.

In addition to that unavoidable portrait overlooking Tiananmen Square, he appears on most of China’s bank notes, is invoked countless times a day in party speeches and remains a staple of state-sponsored TV dramas and movies. This month, however, the Mao industry shifted into overdrive, with restaurants flogging his favorite dishes, cities plastering his sayings on walls and a plethora of statues making their debut — the most notable (ahem, gaudy) of which has been a $16.5 million gold version inlaid with gems….

Mao’s home town of Shaoshan has spent $320 million in preparation — renovating historical sites and museums, organizing galas, and building new roads and other infrastructure. Hundreds of thousands of people are expected to pass through. Many hotels have been fully booked for days leading up to the anniversary. Merchants in town say they have stocked up on Mao tchotchkes of every kind — busts and statues, key rings, commemorative liquor, little red books of his sayings and photos from every phase of his life.

A $16.5 million golden statue of Mao studded with gems. $320 million to get his home town ready. No, I’ll never stop marveling at the Mao phenomenon.

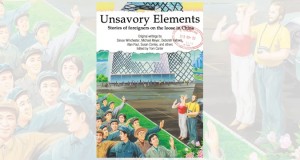

I’m reading a book of essays (book review to hopefully follow soon) about a man whose grandparents and their siblings were exterminated for having been “landlords,” and whose parents were turned on in the Cultural Revolution, and again I wonder, how much suffering can the Chinese people endure, and how can they forgive the man who directly caused so much of the torment? Intellectually I understand it, China’s thirsting for a great leader, and all the propagandizing that’s elevated Mao to the status of a god. But it never ceases to amaze me how short our memory spans can be, and how willing the Chinese people have been to forget the nightmare years and to keep Mao’s personality cult thriving.

The Washington Post article cited above, which is an excellent read, quotes from a vitriolic opinion piece published outside of China that criticizes Mao and his myth; the author, a former aide to Zhao Ziyang, lives under house arrest and had his article smuggled out of China. Referring to the deaths of millions under Mao, the writer, Bao Tong, tells the reporter, “China cannot turn a blind eye to these facts.” But it has been doing a marvelous job doing exactly that for well over 30 years.

Comments