[Note: I meant this to be a brief post about my plans for blogging in the future, and how China would fit into that plan. Then it took on a life of its own. If it is a bit polemical and/or boring, I apologize in advance.]

I’m going through a major change of heart regarding what I want this blog to be. I don’t want to chronicle the malfeasances of the CCP as I used to (though I’ll do so when I think it’s important enough). I don’t want to spend the day proving and re-proving that the Communist leadership in China is evil. This will probably disappoint some readers who come here for the daily litany of CCP sins. But I decided during my last few visits to China that my former approach can be misleading, or at least incomplete.

I saw (and see) what can be safely described as evil in the current system in China. The stories of corruption and brutality against the disenfranchised underclasses are true and they are important. The government’s approach to SARS will always be fresh in my mind, as I was so in the thick of it and saw first-hand just how dreadful this government can be. This topic is usually greeted with a chorus from those who see the CCP as an instrument of positive change: The CCP learned from SARS and they are getting better. I’m still open-minded to this argument. I just haven’t seen enough evidence of it yet.

But I believe now that the CCP is not monolithically evil. I know there’s a number of CCP members who truly hold a vision of a free and democratic China. Such reform-minded individuals have always been a part of the CCP. Unfortunately, they are up against a formidable entourage of party dinosaurs who cannot simply be swept under the carpet. Nice guys in the CCP always seem to finish last.

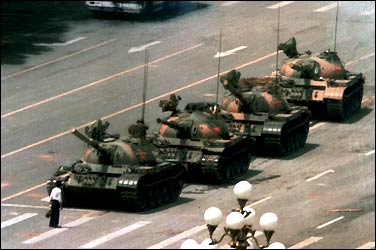

Scanning The Tiananmen Papers, I understand even more just how divided the party has been, and how actively some of its members have fought for real reform. Those who fight against such reformers are not necessarily evil. I think many of them really believe they are doing what is best for the country. But their first concern is their own political survival and preservation of their power base. If, in ensuring their ongoing power, they have to trample on the innocent, it’s a shame, but it simply has to be done. Like an elephant brushing up against a sapling and crushing it. Not malevolent, but destructive nonetheless.

I also have understood for a long time that the current CCP is amazingly similar to the ancient emperors’ regimes, in which government was to be used not for the benefits and protection of its subjects, but for ensuring the survival of its leaders. So the CCP is not so unique in China’s history and it did not materialize in a vacuum. And it’s not going to change drastically overnight.

So while I’m trying to consider all sides of the picture, I’m trying to cut the leaders a little more slack. A little. I remain adamant when it comes to the issue of political reform (though I’d love to be convinced otherwise). So far, the reforms have really been about guaranteeing the CCP’s power, not about diminishing it. In the wake of the Cultural Revolution, Deng had the wisdom to realize that the ongoing descent into radical leftist insanity would ultimately turn China into a nation of isolated, fanatacized cretins. His reforms did as they were intended to: they ushered China into the modern world, gave the people new hope and often new wealth, and set the stage for China to become a true superpower.

But at the heart of it, these reforms were true to the CCP’s traditional ideal of maintaining total power and control, of self-preservation. They totally failed to end the awful caste system, in which the party members are entitled to all sorts of luxuries and privileges, and the subjects are powerless to complain about their leaders’ excess and cruelties. (A bit of credit here: more and more lawsuits are being filed against the government in China, and some plaintiffs have actually won. A teensy-tiny drop in the bucket, but still a positive sign)

The economic reforms have been dazzling, the envy of the world, and social reforms, especially recently, have been impressive. But when it comes to political reforms, we’re still in the dark ages. Yes, there have been some important improvements. Obviously, people are far more free to speak their minds, and some clever journalists are subtly getting out their messages about the government’s failings. And the Internet has become a key instrument in sharing ideas and information, despite the frenzied attempts of the CCP to control it.

But the fact is that censorship is worsening, corruption still reigns supreme and many of the antique laws of the old days contniue to cause the Chinese people terrible and unnecessary grief. I look at one example, the hukou system (a grotesquely unfair entitlement system that determines where a person can and cannot live and work) and I have no choice: I have to conclude some of the most revolting aspects of Maoist rule are alive and well. The word of the day is Reform; it’s all we hear about. And yet, aside from racier magazines on the racks and more sex on TV, we still see no signs of true political reform.

I have some good friends and lots of acquaintances in China who believe in what the CCP is doing. Basically, this faith is generated by the improving quality of life for so many Chinese — more people have more money. This is important. Money can be the determining factor between comfort and misery. Where I disagree with them strongly is that this is the result of any grand scheme of the CCP’s, that they designed it all to be this way. What happened after Deng took power was that he gave the people an inch and they grabbed a mile — once there was room for capitalism, the Chinese — the world’s most capitalistic people — made their own wealth, just as they have done in every country they’ve gone to. (This has nothing to do with race or genetics, but about culture. The Chinese have always been taught to save money, and to use it to make more.)

As far as trade and commerce goes, I think the CCP has been a bungler, hardly the geniuses some would have it. The people made their money because the government got out of their way, not because the CCP offered great financial wisdom. With foreign trade, the party deserves even less credit. Ask any foreign company doing business in China what kind of hoops they had to jump through and how many palms they had to grease along the way. It’s as though the CCP has put up every conceivable obstacle to real free trade for outsiders. This is a key component of the corruption system that keeps party members rich and that created the “princeling” phenomenon.

My friends who are more positive about the CCP always tell me that the sheer size of China’s population makes it impossible for the government to control what its local cadres are doing. These cadres, they tell me, are the source of many of the evils and the CCP cannot be blamed for their crimes. The CCP is more concerned about the massive general population, not about a group of AIDS patients who are beaten up by local police, or of a group of coal miners jailed and tortured for protesting the outrageous taxes collected by their local leaders.

There’s a lot of truth to this. When we’re talking about a population so vast and distributed over so much space, controlling what happens in each village is a dizzying challenge. And yet, and yet….

Let’s look at how well China has done in controlling this vast population from Mao to now. Every single person is registered in the aforementioned hukou system. Meticulous records are kept on most of them. Government checkers go door to door of every home and make sure the women are not producing too many babies. About 30,000 government bureaucrats spend their entire day watching the Internet for signs of subversion. Under Mao, the type of corruption that runs rampant today was trifling. It was controlled. (Of course, this was more than compensated for by mass murder, famines and unspeakable tyrannies.) So is it really so impossible to keep the behavior of local cadres in check? Or is this corruption the main reason cadres remain loyal to the CCP? Is it insurance against disloyalty? I can’t say for sure, but it’s something to think about.

So those are some of my personal feelings about the CCP. But as I said at the start, I’ve tempered some of my animosity because I believe there are forces at work for real change and increased freedom. I know it takes time, and there really are risks of moving too quickly. But Deng seized power more than a quarter of a century ago. I’m not convinced that constantly allowing them more time, showing patience and understanding, giving them “space” and always forgiving their excesses as “teething pains” — I’m not convinced that such coddling is the way to go. Look at SARS: It wasn’t coddling and patience that brought about the extraordinary press conference in which the party actually admitted its crimes. No, it was the international outcry, precipitated by a Beijing whistleblower and brought to a crescendo on the world’s editorial pages, that blew the CCP’s cover and literally forced them to account for themselves. The soft and gentle approach might at times be appropriate, but the evidence tells me they are more likely to respond to international pressure. Pressure that threatens investment and damages the reputation the CCP has worked so painstakingly to build over the past ten years.

But even after saying all that, I have more hope than I did before, if only because the dinosaurs are dying out and the new generation appears more open to democracy and real freedom. My attitude is, keep up the pressure, call them on their misdeeds, but don’t approach them as a force of pure evil. Our best hope is to continue to lead by example, so the new generation of leaders continues to see liberty and democracy as goals to strive for.

So back to my blog. I am finding it really difficult to maintain Peking Duck’s persona as a China-focused blog. I am going to try, but as I said, I’m not inclined simply to list all the CCP’s outrages or to scold them ad infinitum. So please don’t be surprised if this blog focuses a little more on US politics and my personal situation, and a bit less on China. I think it will always be a China blog; I feel too attached to the community to simply give it all up. But it can’t be quite the same as when I was living and working in Asia.

Thanks for your patience if you made it to the end of this over-long and all-over-the-place post.

[Updated at 4:50 pm Mountain Time]

Comment