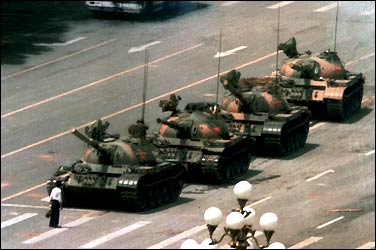

Below is the interview I posted a few day’s ago on Living in China. It tells of the evolution of a former flag-waving protestor in the 1989 demonstrations in Shanghai. If you’ve ever looked back at the Tiananmen Square days and wondered what those students are doing and thinking today, you may find this interesting.

David S., 34, is now a prominent executive with a multinational technology company here in Singapore, and I’ve been lucky enough to work with him on his company’s public relations. When I heard that David played a part in Beijing’s sister demonstrations in Shanghai, I asked if I could interview him about the role he played and how he looks back on those days nearly 15 years later.

What made this so interesting for me was seeing the evolution of a 1989 demonstrator, from flag-waving rebel to a proud supporter of China and its government. It is a remarkable story.

Some of David’s viewpoints are quite different from my own, but that isn’t relevant. At the end, I offer a few of my own thoughts, but I don’t want to editorialize about which point of view is right or wrong.

Q. What brought you to the demonstrations in Shanghai?

It’s hard to understand this if you weren’t there, but it would have been abnormal for me not to go to the demonstrations. We all went, it was just natural. My classmates and I were swept up, we simply had to go, it was the natural thing to do. Suddenly, we were all participating.

You have to be aware of the situation in China at that time. It was as though there were two parallel systems, one being the economic system, the other the political system. These systems were like two wheels that weren’t on level ground, and along the way tension built up over a period of nearly 10 years, ever since Deng came back to power after the Cultural Revolution. That tension was tremendous, and no one could escape from it.

Chinese society consists of multiple layers – peasants, students, soldiers, factory workers. At that time, there was tension at every layer of the society. People were confused and frustrated. Earthquakes happen when different layers rub against each other at a different pace, and finally the earth can no longer contain the energy and it erupts. That’s the type of tension that was behind the protests.

So much about the economy had improved and was changing, but politics – the government – remained status quo. In the 1970s, if you said anything disrespectful of Mao, you’d be executed. In 1989, if you said something negative about Deng in public you could still be in serious trouble.

It was the students who were most sensitive to this. Our parents all worked for the state, and there was still little or no private enterprise. They were not as concerned about ideology and change. They only had to worry about feeding their families. But as students we were more liberal, more free-spirited and more engaged in ideologies. We weren’t concerned about raising a family. We were not necessarily practical; we were very idealistic.

Historically, most great movements in China were started by students. Even today, we celebrate China Youth Day on May 4th. That’s because when the KMT [Kuomintang] were still in power and the Communists were outlawed, the students demonstrated for the Communists on May 4th. General Tuan Qi Rui was the warlord over Beijing at the time and he opened fire on them in the street. So after the Communists took power they dedicated that day as the nation’s youth, which is still a holiday today.

Q. Where were you, and what was your own role?

I was studying medicine at the Shanghai Second Medical University, now a part of Fudan University. I was asked by my classmates to be the flag bearer because I’m quite tall, so my role was to carry the flag and wave it in front of the demonstrators. Every day we would march from the university campus all the way to the People’s Square, and I was in the front holding and waving the flag.

Q. Looking back, are you glad you did it? Do you have any regrets?

No, I don’t have regrets and I don’t think what we did was in vain. It was important for us to make our voice heard. For my generation, the crackdown had huge implications for our lives, probably like the JFK assassination had for Americans.

But I have to admit I am no longer interested in politics, especially now that China is undergoing a natural transition toward democracy, with the economy being the core and the catalyst for that change. And nothing can stop that change, no matter how much the Communists want to preserve their old values.

Q. We all know about the violent crackdown in Beijing. How was it handled in Shanghai?

There was nothing like the martial law that took place in Beijing. The Mayor of Shanghai at the time was extremely competent, and he made an appeal to the city on TV and he calmed everyone down. I’ll never forget, he said something that was ambiguous and politically brilliant: “Down the road, truth will prevail.” That could have meant he was sympathetic to the students or totally with the government. But it was very calming to hear him say it.

The mayor organized factory workers to clear the roads, not the army. These workers were the parents and uncles and aunts of the students. Some members of the student body tried to stir up these factory workers, and I think that was a very dangerous thing to do. Students demonstrating was one thing, but if it was factory workers – that would need to be stopped, and there would have been a riot. That’s why Beijing was much more tense.

Bringing in the factory workers truly showed the leadership and tact and common sense of Shanghai’s mayor – Zhu Rongji. Beijing is the political center, but Shanghai is the financial center, and it could absolutely not fall into chaos, no matter what. That’s why you saw factory workers and not the army.

Q. How did you hear of the massacre, and what effect did the news have?

My father and I heard about it on the radio, on ‘Voice of America’. That was the only source there was. Soon we all knew what had happened. We watched CCTV the next day. The reporters were wearing black and some of them were obviously in a deep state of grief, their eyes visibly red, as they announced that the anti-revolutionaries had been put down. I saw those reporters with my own eyes, and soon afterwards they were replaced.

At the moment the news broke of the crackdown, I was angry. How could it happen? All of the demonstrations were peaceful. How could they justify tanks and machine guns? I gave up all hope in my own government, and I felt ashamed to be Chinese. We were also disappointed in [then] President Bush – he was softer than we wanted. All that Bush did was impose sanctions, and that disappointed us. We were in a dilemma. We wanted the US and others to do something, but we also knew that would have hurt us.

That was part of being 20 years old in China when you haven’t seen the world, no Hollywood movies, you’ve only read Stalin-style textbooks. I matured ten years overnight, and I also became a little cynical.

For so many years China had a stringently controlled educational system. From kindergarten to college, we all read the exact same books and took the exact same exams. We always believed everything that the government told us, and they told us it was an honor for ‘the people without property’ to shed their blood and sacrifice their lives for the cause of communism, fighting against the two great enemies, the Nationalists [KMT] and the Capitalists. We were brainwashed.

After Tiananmen Square, most of us believed that all government was evil. We saw that our government would kill us. I remember how my aunt told me she went to the Tiananmen Square area shortly after the crackdown and there was someone saying through a megaphone that there had never been any shooting even though she could see the bullet holes on the walls, which were soon cleaned up.

But now, that sense of shame is gone. When I look at it all objectively, I believe the government did the right thing. Maybe they didn’t do it the right way. I still have reservations about the tanks and the machine guns. But at that time they couldn’t afford to sit down and negotiate. The students wanted power, and in 1989 the social cohesion wasn’t there to support that. It was only 10 years after the Gang of Four, and it wasn’t like today. In retrospect, Deng at that time couldn’t afford to show further weakness. He had to hold the country together. Yes, we paid the price in blood, but we are still one country, one nation.

You have to realize that Deng changed my life – everybody’s life. He opened new doors for all of us. In 1982, my mother was among the first batch of scholars who were sent abroad to study, and she went to Harvard. She returned to become the director of a major Shanghai hospital. So we are grateful. And soon so many other changes happened.

I feel a great respect for our leaders. There are some, like Li Peng, who I still have no respect for. But Deng – soon we felt as though he had torn down the Berlin Wall. I wondered, if Deng had not handled the demonstrations the way he did would China be the country it is today? The whole nation is changing and people are more affluent, and I feel proud of being Chinese. People once looked down at us, and now they have respect for us.

Q. But what Deng achieved – could he not have done it within a more democratic system? Did there have to be the ruthlessness?

After going to the US for five or six years, I saw that the level of democracy there can only happen in a society with a certain level of education. What the people of China now need is leadership. China is one century behind the US, and you can’t expect us to change that fast.

This is why many Asians resent it when Americans try to insist that the Chinese adopt their style of democracy. Shanghai may be ready, but if you go out to the surrounding areas, you’ll see it just isn’t possible, that it will take more time. I believe that one day, China will have Taiwan-style democracy, but it has to be built on a strong economy.

Q. I agree that Western-style democracy isn’t right for China today. But can’t there be a compromise? Can’t the government be strong, without tolerating abuse of the poor by corrupt officials, without tolerating the marginalization of AIDS victims, without arresting kids who write about government reform on the Internet?

The way we view human rights is so different from the West’s. We have 1.3 billion people and many of them go hungry. Putting food on the table and a roof over its people’s heads is what our government has to worry about. AIDS, corruption, the Internet – that is all secondary to the leadership of 1.3 billion people. If I were running China today, I would not be able to hear all the different parties. I would have to have my own agenda and stick to that agenda. I believe that if a secret vote were held today most people in China would vote for the CCP.

For more than 150 years, starting with the Opium Wars, our national pride has been bullied by the Europeans, the Russians, then the Japanese. Now China is an economic and a military power. And it has no intentions of being aggressive. So I am not giving up my Chinese citizenship. Ten years ago I would have jumped to do that.

Looking back, I firmly believe the government did the right thing, though they could have handled it better. We paid a high price. Our leaders in 1989 could have shown greater human skills and greater negotiating skills. But let’s live with Communism for now and change things one thing at a time. The Chinese now have a much better life than they did 100 years ago. Not so long ago, my house was the first in our hutong to have a television set. The whole neighborhood would come to our backyard and sit on the ground to watch. It was just a 9-inch TV, and we put a large magnifying glass in front of it so everyone could see – that is how inventive we Chinese had to be. And now, so many families have two color TVs. They enjoy a better life, they have pride, they just put a man into space. Over the next couple of decades, China will probably overtake Japan. The world now needs China as much as we need them.

Thank you, David.

This was definitely an eye-opening interview for me. Coming from my own background where the rights of the individual are sacred, I was intrigued to hear such a different point of view. As readers familiar with my writing know, I am not quite so easy on the CCP, and don’t feel all can be forgiven under the mantra, Change must take place slowly. But I have the highest respect for David, and find the story of his transformation and his great personal success to be impressive and inspiring.

Comment