I probably don’t have to tell anyone here that I am a serious Peter Hessler fan. I took a circuitous route along the way, starting with Oracle Bones and then River Town. My friends told told me I should have started the other way around, and even though they were right, it hardly mattered. I loved them both.

Hessler set the bar impossibly high with River Town, and it’s almost sad – there is simply no way he can surpass it. An almost perfect blend of memoir, tour guide and history lesson, River Town is by far the most personal and moving of the three books (now including Country Driving) and, significantly, it’s the most coherent. It seems to flow effortlessly, without a lapse anywhere. The voices of his characters, like his uptight Chinese teacher, linger in your memory for a long time, maybe forever (“Bu dui!”), as do his students’ essays on a Shakespeare sonnet and Robin Hood. And you have no choice; you simply have to keep turning the page.

Oracle Bones is more demanding and less cohesive. Or maybe it’s more demanding because it’s less cohesive. It weaves several plot lines together, like the adventures of his Uyghur friend Polat, and the challenges faced by his former students, uprooted from home, some working in a Shenzhen factory. But it’s also about archeology and history, about the Chinese language and the Cultural Revolution. For me, the most gripping scenes were those in which Hessler traces the tragic fate of oracle bones scholar Chen Mengjia, who was denounced by a colleague during the CR and took his life. Relentlessly Hessler tracks down those who knew him and, ultimately, the man who denounced him. Their meeting is another of those moments when I simply had to put the book down and reflect; this man had done a terrible thing, and yet he was not a terrible man. This was simply what China was at the time, this was simply what you did. Like all personality cults and forced utopias, you look back and see insanity, though at the time it was simply what you did every day.

(I had similar feelings reading The Man Who Stayed Behind, and a few months ago Rittenberg was in Phoenix giving a talk. I asked him how he could describe in his book his revulsion at much of what he saw going on at the time, while simultaneously describing his active participation. “I surrendered my critical thinking,” the 81-year-old former Communist replied. “We all did.”)

But back to my point: There are so many things going on in Oracle Bones, which a friend described to me as a pastiche of Hessler’s New Yorker articles), that at times you can’t help but feel it’s meandering. It’s Hessler’s mesmerizing story-telling ability that holds it together. You kind of know it’s disjointed, but it’s so fascinating you don’t care. But it doesn’t come close to River Town in terms of pathos, or poetry. River Town is poetry.

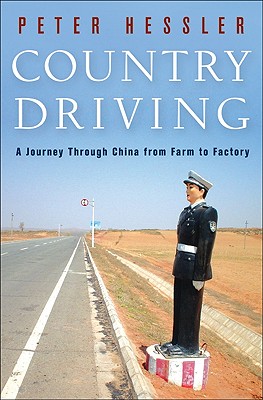

And so we come at last to Country Driving, Hessler’s latest, a savagely funny and delightful read, and, like his earlier works, a combination of travelogue, colorful yarns, history (especially the history of the Great Wall), intensely personal profiles of individuals caught between the shifting social and economic forces of today’s China – all held together by the common thread of country driving.

Like Oracle Bones, this book is unashamedly disjointed. It is actually three separate books stitched together, perhaps a bit awkwardly, but again Hessler makes it work. The first (and funniest) section is mainly about the Great Wall, Chinese road maps and Hessler’s driving test. It’s punctuated with snippets from the written test he was given, with gems such as this:

If another motorist stops to ask you directions, you should

a. not tell him

b. reply patiently and accurately

c. tell him the wrong way.

Or:

When driving through a residential area, you should:

a) honk like normal

b) honk more than normal in order to alert residents

c) avoid honking, in order to avoid disturbing residents

That questions like this can even exist on a driving exam boggles the mind. Could there possibly be drivers who feel the best practice is to give false directions, or to honk the horn when entering a residential area? There must be, and a lot of them must be in China. (I think we all have a story to tell about horn honking in China.)

Roads and driving are the pervasive motifs in all three parts – what it’s like to drive along the “Great Wall” (of which there are so many) deep into the heart of China, how China’s new roads make or break communities, how they offer new worlds of opportunities to once isolated villages, and how a lot of Chinese drivers aren’t so good behind the wheel.

Along the way, as always, Hessler digs up nuggets of history and makes wry observations that ensure his journey is an entertaining one. Perhaps my favorite was his description of a book of maps that perfectly captures the Chinese psyche in regard to territories it sees as “part of China.”

A company called Sinomaps published the book, which divided the nation into 158 separate diagrams. There was even a road map of Taiwan, which has to be included in any mainland atlas for political reasons, despite the fact that nobody using Sinomaps will be driving to Taipei. It’s even less likely that a Chinese motorist will find himself on the Spratly Islands, in the middle of the South China Sea, territory currently disputed by five different nations. The Spratlys have no civilian inhabitants but the Chinese swear by their claim, so the Automobile Driver’s Book of Maps included a page for the island chain. That was the only map without any roads.

I’m fairly sure that to anyone from outside of China this would seem somewhat puzzling: a driving map with no roads, and maps of roads on which the publishers know their readers will never drive, placed in the book as a matter of principle. You know you’ve lived in China too long when things like this don’t strike you as absurd.

The other unforgettable image he conjures up is that of the fiberglass Chinese highway patrol officers that dot the freeways, terracotta scarecrows reminding citizens to drive safely.

There was something eerie about these figures: they were wind-swept and dust-covered, and the surrounding desert emphasized their pointlessness. But their posture remained ramrod straight, arms at attention with a sort of Ozymandian grandeur – terracotta cops.

Just as with the driving maps of Taiwan and Spratlys, the reader can only ask, “Why?” And the only answer is, this is China.

To briefly summarize the other sections: Book two is all about Hessler’s second home in a village north of Beijing. This is a radical departure from the previous section, in which there are no anchoring characters aside from Hessler himself, only strangers he meets for a moment on his travels and their fleeting stories. Now it’s all about one family and how the new roads to their village change their lives. This is much more like River Town, full of humanity and characters who you come to love, grappling with a world that puts their traditional culture on its head.

Book Three is about Hessler’s stay in Zhejiang province, where he tracks the birth of a factory that makes little rings used for the straps of brassieres. This chapter is all about the “New China,” the flood of migrant workers to the factory towns, the wheeling and dealing behind the scenes, how the workers are hired and how they live.

The recurring thought I had as I read this chapter was of just how little most Westerners know about migrant workers and their lives. I’ve read countless articles about the slavish conditions in which they live and the torturous hours they’re forced to work. And while that’s often true, it doesn’t tell the whole story. Most of the workers Hessler describes want to work the long hours. The last thing they want is vacation time. They want overtime, and they want to work on the weekend, as much as they can. They’ve come to the manufacturing towns for one reason, and one reason only: to take back as much money as they possibly can for their families. Hessler shatters quite a few myths here.

I can’t go into the details of these three books stuck together as one. (I fly to Shanghai in 12 hours.) But here’s the main thing: Everyone who would read this blog should get a copy of Country Driving. My bigger wish, however, is that people who aren’t so familiar with China get to read it, too. There is such a plethora of articles on China, mostly bad, flooding the Internets and the newspapers, and Hessler’s book, like his earlier two, provide wonderful antidotes, stripping away all the pompous claims of the “China experts” (something I freely admit I will never be) and showing you…China. The real, unvarnished China, free of editorial bloviation and spin. A dizzying, breathless, magnificent country, irrepressible in its energy and ambition, often irrational, unjust and infuriating, and always unpredictable. And often achingly funny.

My main issues with the book: It really is disjointed, and unlike with Oracle Bones, you really feel the bumps. Also, I found that Hessler often tries to be funny in this book, something he doesn’t do in the earlier books, and it doesn’t always work. The thing is, he doesn’t have to add jokes; his anecdotes are hilarious as they are, and inserting bits of cutesy humor isn’t necessary.

But these are small nits. Country Driving is a beautiful read. It may not have the hypnotic force of River Town, but what does? It’s a very different type of book, much more sweeping in its focus if not quite as intimate. If you really want to know modern-day China it’s simply indispensable.

Comments